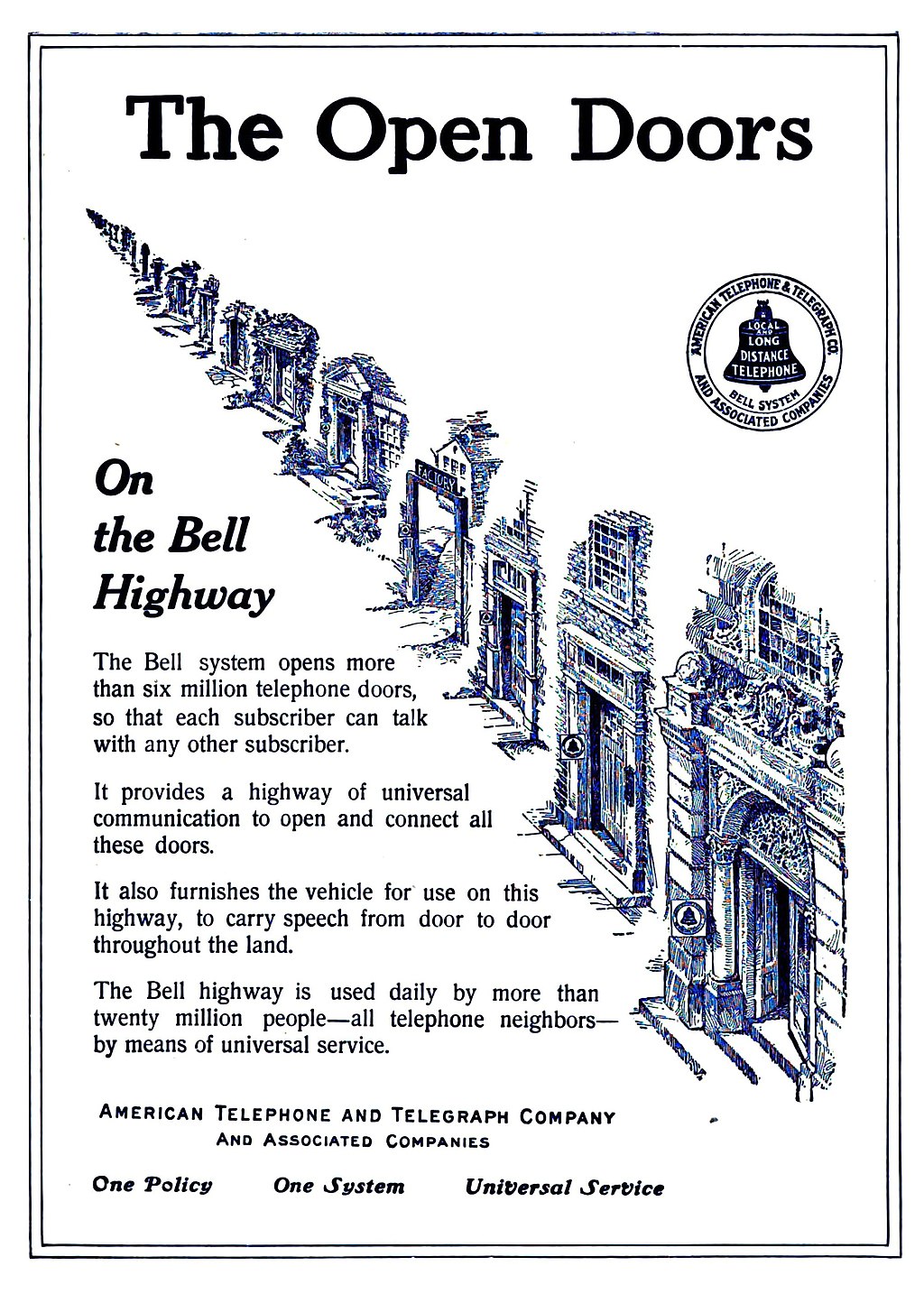

There was only one phone company. It was known as Bell System. It was a federal government regulated monopoly. It was so ubiquitous and universal, that people tried to humanize it by calling it “Ma Bell.” Phones had cords, and they all came from Bell. If you wanted to make a local or long distance phone call, you had one choice: Bell System.

With no direct competition in telephony, the main purpose of advertising was to encourage people to use the telephone to make calls. Local calls burgeoned. Long distance calls lagged. Why? Because LD calls were charged both by time and distance. This made perfect sense from Bell’s perspective, as the sole operator utilized its system assets which were measured by time and distance – it cost a lot to install and maintain wires and switches. Since profits were limited and regulated by government, the Bell System could not be tempted to raise prices without explicit permission to do so.

The company I worked for, N.W. Ayer & Son, became the advertising agency of Bell System in 1906. (I’m old, but not so old that I was there at that time). Our early ads for Bell were paragons of simplicity, using analogs to foster realization of “invisible” service.

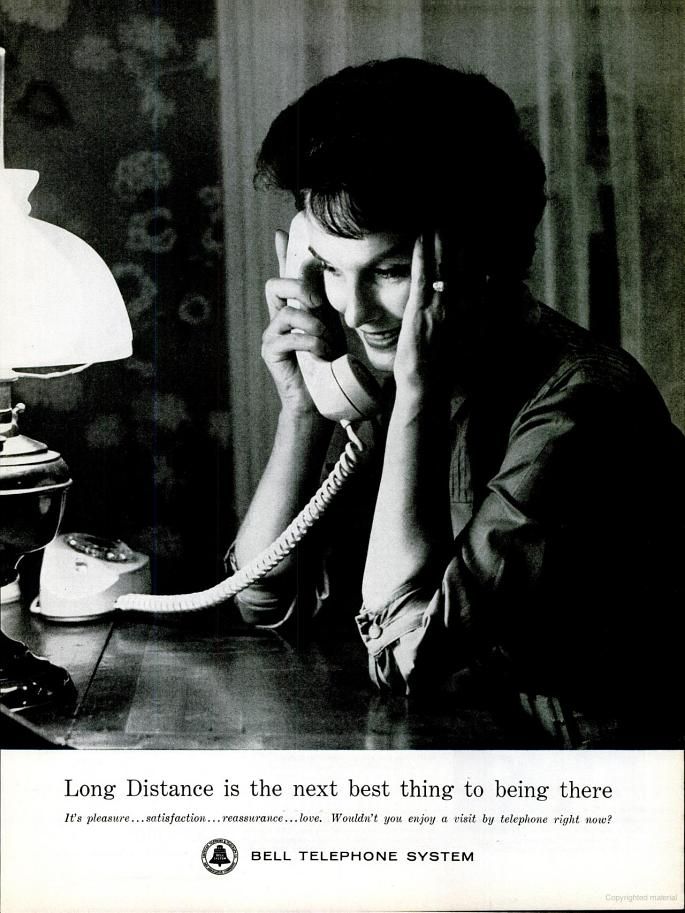

By the 1960’s, Ayer utilized other analogues, with the goal of encouraging system usage.

“Next best thing” was apt, but didn’t cut it. Bell System usage fell short of potential.

Ayer learned from the callers’ standpoint that “next best thing” made them instead think about the “real thing” of being there. We also learned that many folks heard an “invisible clock” ticking in their heads, even before picking up the phone. Often, this mental affect deterred people from making a call, even before picking up the phone.

We needed to get much closer to the human truth of what a phone call means to people. Ayer figured out how to do it for them, and with them, with spectacular results.

For that story, look for my next Admeritus post, coming soon on a computer near you!